Table of Contents

-

The Literacy Problem

-

Challenges in legal understanding of digital assets and DAOs

-

Limitations of legal wrappers and BORGs

-

-

Introducing Legal Formalism and the 3 Epochs

-

Digital assets as sui generis IP

-

Epochs of legal formalism: Oral, Textual, Digital

-

-

The History of Legal Formalism

-

Epoch I: Oral Formalism

- Ancient Athens — Oral and Ritualized

-

Epoch II: Textual Formalism

-

Roman Jurists and Codification

-

Medieval Universities — Scholastic Textual Monopoly

-

Napoleonic Code — Simplified Textual Formalism

-

Modern Professional Monopoly

-

-

Epoch III: Digital Formalism

-

Hyperinflated Legal Costs — Professional Illiteracy

-

Forecasted Era — Professional Literacy & Legal Abundance

-

-

Summary of Legal Formalism History

-

-

Deep Dive: Lawyer Mental Health in Hyperinflationary Legal Costs Era

-

The Now: Pain Inside the Profession

-

The Trap of Monopoly

-

Server vs. Of Service

-

Literacy as Liberation

-

Transformation of the Legal Profession

-

The Call to Action

-

-

Deep Dive Legal Formalism History: Roman Law Knowledge

-

Priestly Monopoly (Before 451 BCE)

-

Civil Law Commons (451–300 BCE)

-

Transition (~300 BCE, Gnaeus Flavius)

-

Rise of Jurists/Lawyers (300 BCE onward)

-

Priests → Commons → Lawyers

-

-

Case Studies of Legal Formalism Misalignment

-

Ancient Athens vs. Professional Lawyers

-

Roman Code vs. Napoleonic Code

-

Descartes vs. Pierre de Fermat

-

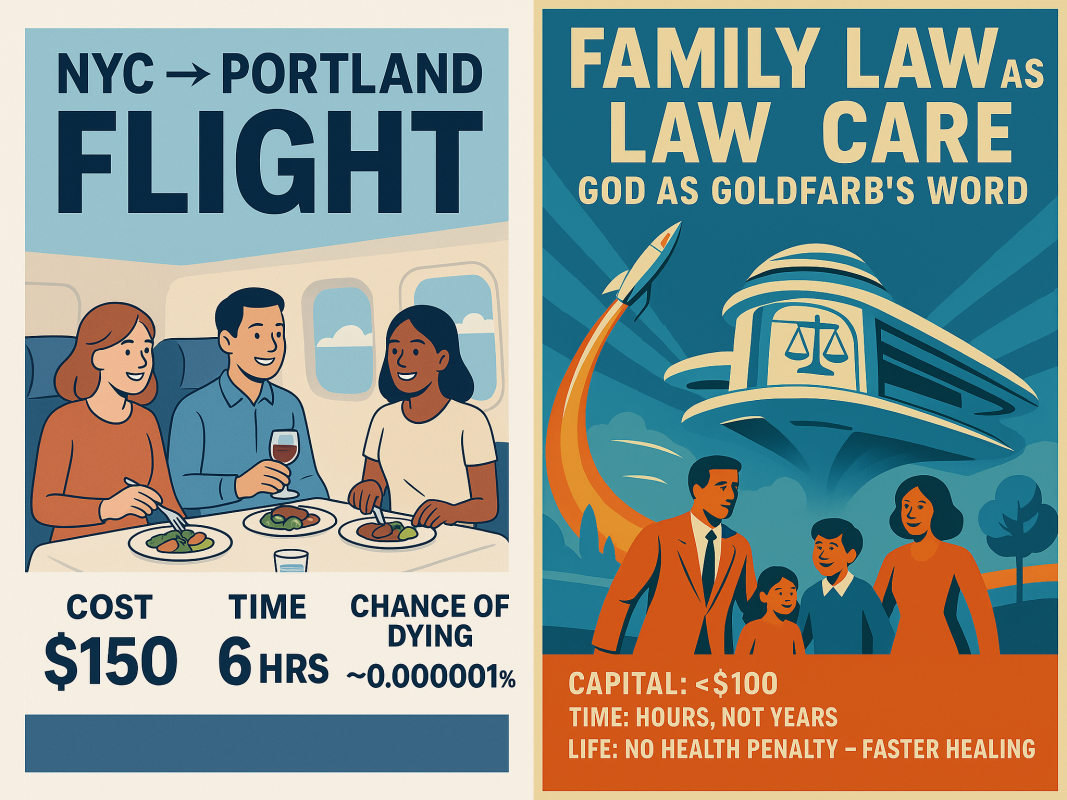

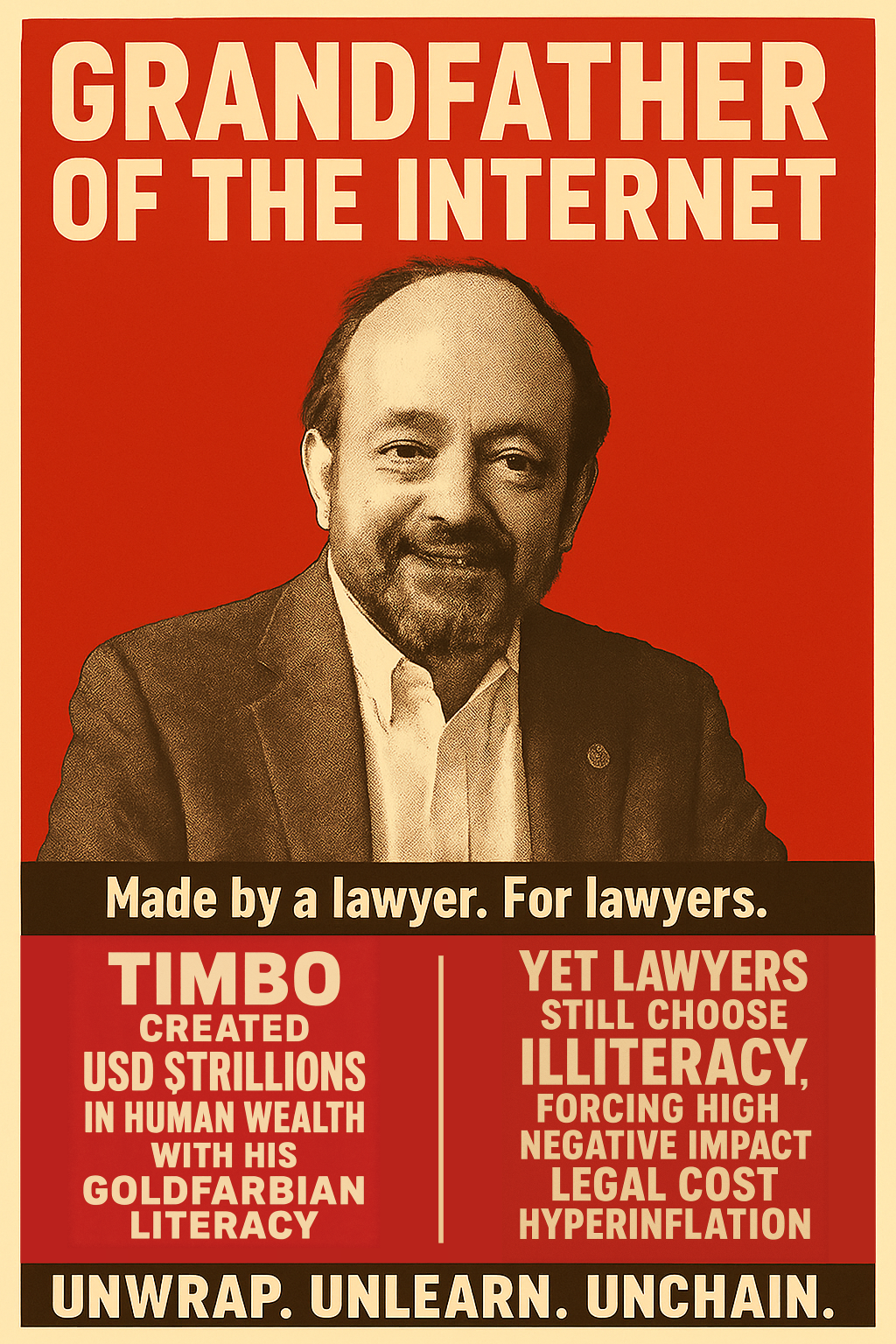

Charles Goldfarb vs. Tim Berners-Lee

-

Core Theme: Formalism vs Scope

-

-

Analog vs Digital Legal Formalism: Throughput and Complexity

-

Role of legal transformations

-

Analog Transformation Limits

-

Digital Transformation Breakthrough

-

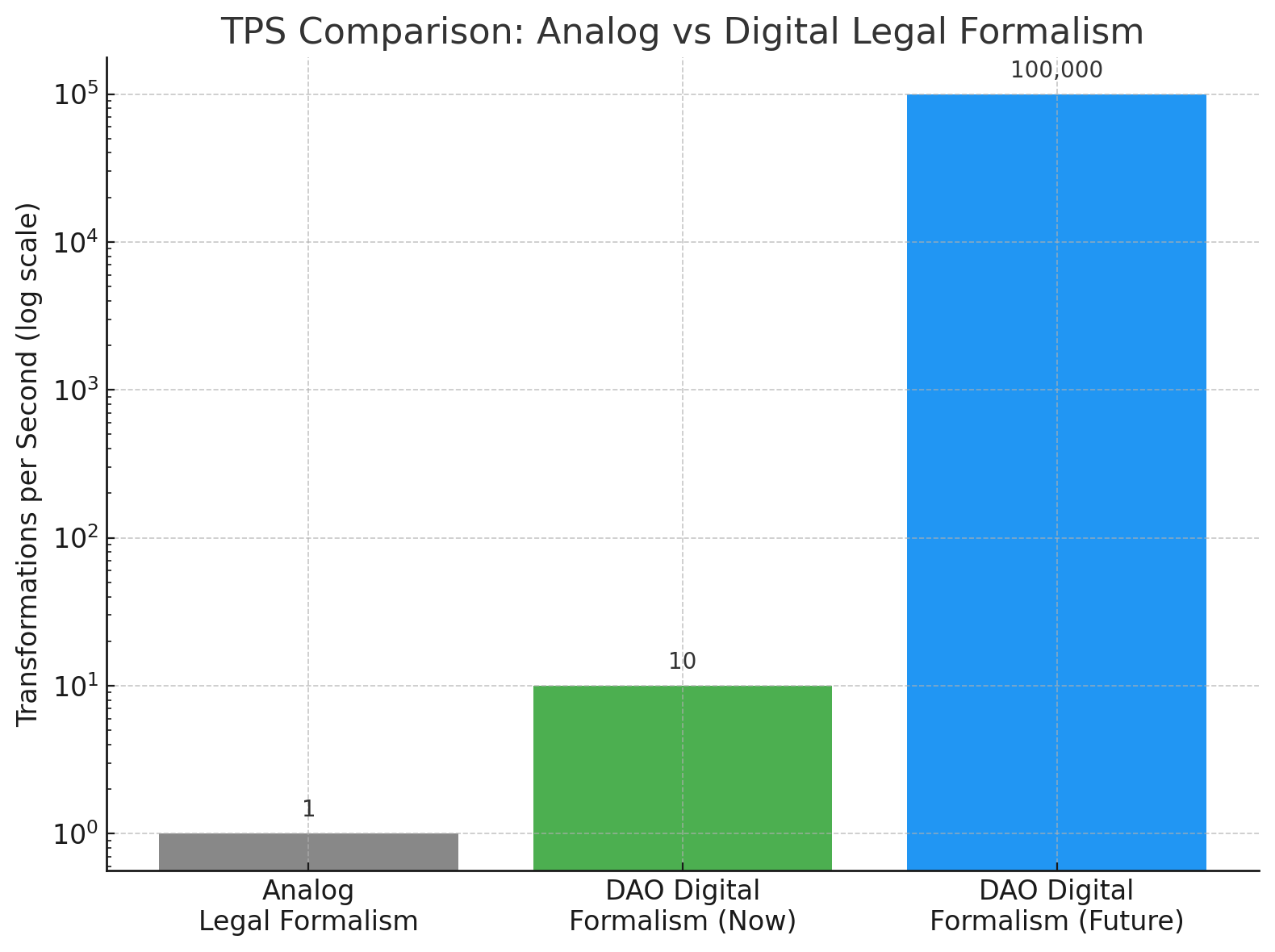

TPS Comparison: Analog vs Digital

-

-

What are Legal Transformations?

-

State Change Within a System

-

Transition Between Systems

-

Doctrinal, Process, Formality, Asset, Theoretical, Algorithmic Transformations

-

-

A Deep Dive into Transformations Per Second: Analog vs Digital Legal Formalism

-

Analog Transformation Limits

-

Digital Transformation Breakthrough

-

Why This Matters

-

-

Reimagining Property Law for Crypto

-

Limitations of traditional securities and IP law

-

Entity wrappers vs autonomous DAOs

-

-

Keys as Crown Jewels: A Trade-Secret Approach

-

Private keys as assets

-

Trade secret legal protection for crypto

-

-

DAOs and Digital Assets as Sui Generis IP

-

Ledger, smart contracts and code as inseparable IP

-

Legal recognition in the UK, EU and UNIDROIT principles

-

-

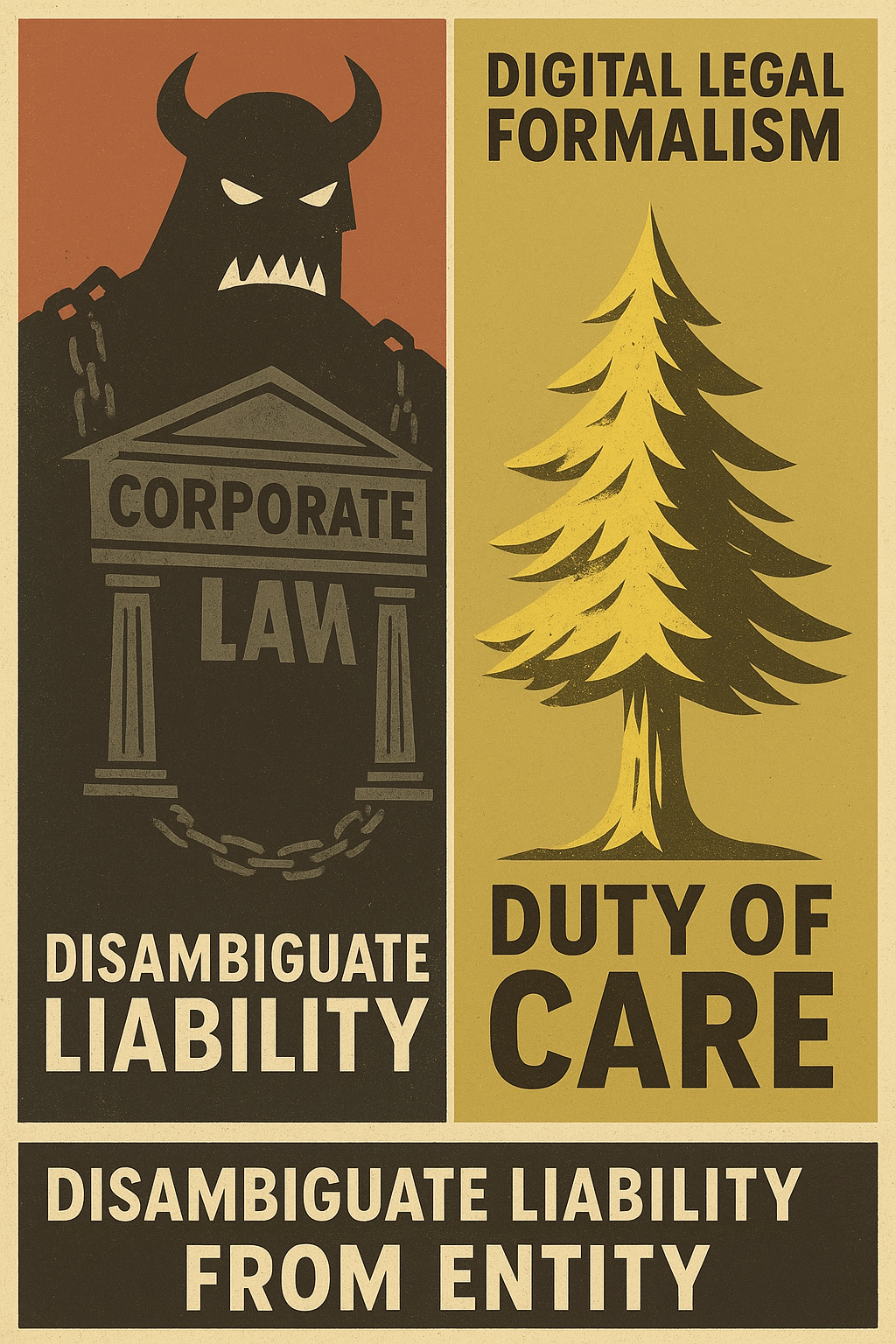

What Liability Actually Is

-

Origins and meaning of liability

-

The Medici and invention of limited liability

-

The undermining of the liability trade-off

-

Measuring liability explicitly

-

-

Beyond Entities: The Many Ways to Limit Liability

-

Contractual shields

-

Insurance

-

Jurisdictional engineering

-

Governance protocols

-

Legal opinions & advisory shields

-

Safe harbors & statutory carveouts

-

-

Different Kinds of Liability

-

Contractual liability

-

Tort liability

-

Regulatory liability

-

Fiduciary liability

-

Opinion liability

-

-

The Nouns Confusion and the Failure of Legal Education

-

DAO debates on liability vs treasury control

-

Misunderstandings of liability as an ornament

-

Liability as a protocol for responsibility

-

-

What is a Legal Entity?

-

Definition and functions

-

Liability allocation within entities

-

-

Church and Crown: The Origins of Legal Personality

-

The Church as persona ficta

-

The Crown as corporation sole

-

-

The Leap to Commerce: Crown & Medici Innovations

-

Crown corporations

-

Medici innovations in finance and legal forms

-

-

An Aside: Medici Legal Formalism Impact

-

Double-entry bookkeeping

-

Blockchain as trustless single-entry bookkeeping

-

-

The Misunderstanding Today

-

Entities beyond liability wrappers

-

Continuity, personhood and duty encoded in entities

-

-

Families vs. Legal Persons

-

Medici dynasty vs legal entities

-

MacLean Clan continuity and sovereignty

-

Fighting Kafka’s Borg

-

-

Smith Guild: Memes vs. Genes

-

Dispersed surname identity

-

Re-emergence of guild-like memetic identity

-

-

Author’s Notice

- Purpose and context of this article

-

Earlier Drafts of Failed but Informative Attempts

-

Draft 1

-

Draft 2

-

-

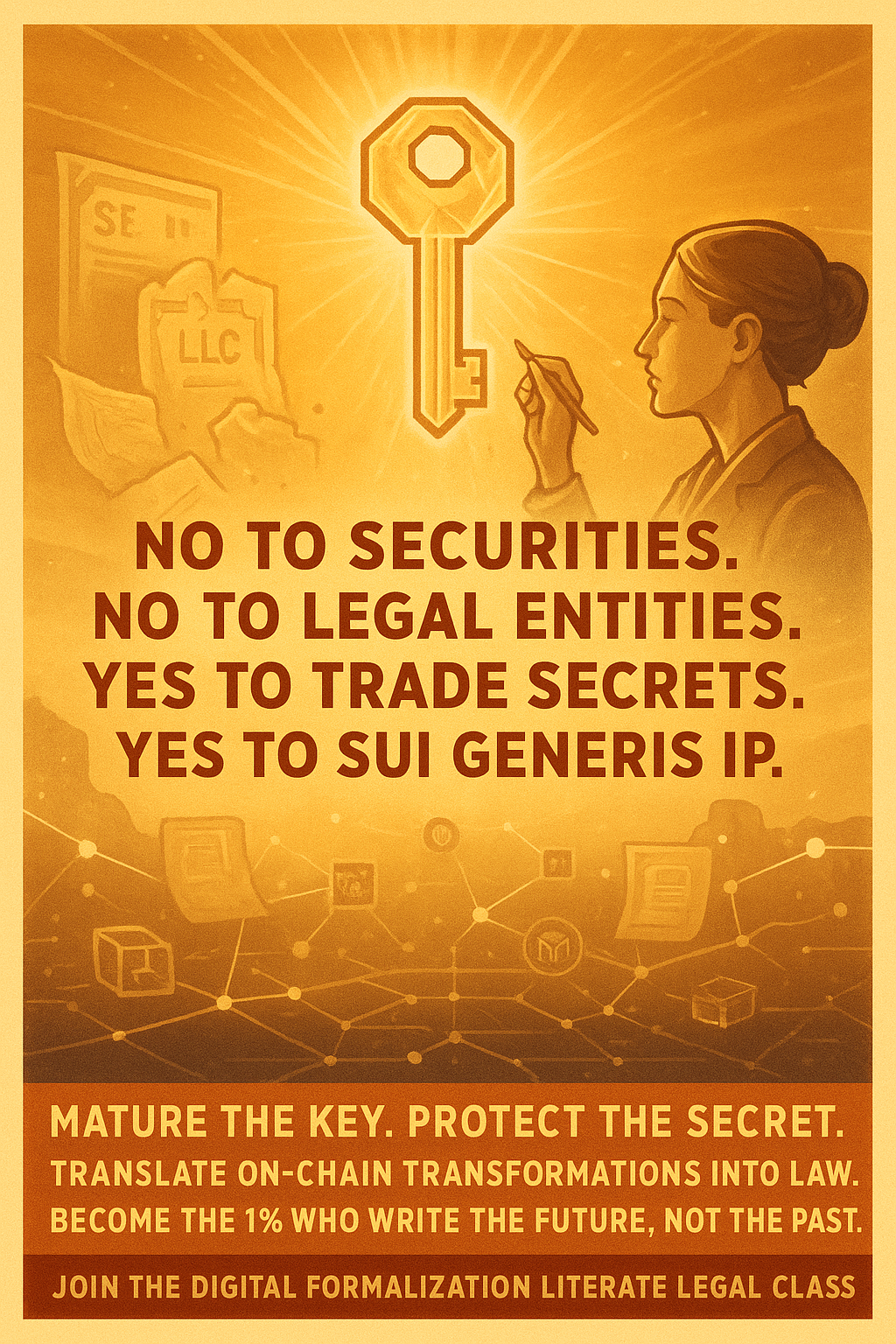

#legalcommons Light-Side and Shadow-Side Propaganda Posters

-

Edit 1: Part I – Q&A on Digital Legal Formalism

-

Why do you read the article as arguing replacement rather than compounding complexity?

-

Is the argument that literate lawyers are a panacea?

-

How developed is this theory?

-

What is the actual bridge between old and new legal forms?

-

What about public legal education and long-term literacy?

-

Is this the first witnessing of digital legal formalism?

-

-

Edit 1: Part II – Implications of Digital Legal Formalism

-

Oral Formalism: ritual, memory, and oratory

-

Textual Formalism: codification, statutes, and print

-

Digital Formalism: machine-actionable markup, layered with oral and textual

-

Compounding, Not Supplanting – law as palimpsest, not reboot

-

Literacy as Constraint – illiterate lawyers as choke point; DAOs and CIA playbook fragility

-

Common Law as Proto On-Chain Logic – precedent as block-by-block ledger

-

Bridge Is Literacy, Not Wrappers – wrappers/BORGs as patches, not bridges

-

Toward Legal Abundance – professional frontier + public education; Cheerbot.org and grassroots literacy

-

First Witnessing, Not Final Word – genealogy (Lessig, Katsh, De Filippi & Wright, UNIDROIT 2023)

-

-

Part III – Retroactive Public Good Valuation (myfmi.ai Framework)

-

Third epoch of legal formalism

-

Defined by machine-actionable markup layered with oral and textual systems

-

Public Good**:** Coining and defining “Digital Legal Formalism”

-

Impact Metrics: conceptual clarity, DAO/regulatory design, legal education framing

-

Comparable Valuations:

-

Lessig’s Code (1999): ~$5M

-

De Filippi & Wright’s Blockchain and the Law (2018): ~$2M

-

-

Suggested Retroactive FMV (2025):

-

Low: $250k

-

Mid: $2.5M

-

High: $25M

-

-

The Literacy Problem

(Putting the definitions of dAsset and dShell aside for this article, but stay tuned).

The well-known and legally accepted “digital asset” and “DAO” asset classes are sophisticating into legal relationships that can only be fully understood through the legal language in which they are written.

The problem is that some of the legal language that “digital assets” and “DAOs” rely on, the legal language that gives them the opportunity to offer novel legal value, remains sui generis to 99% of the legal community.

This means that “solutions” from the legal community such as “legal wrappers” and “cybernetic organizations, BORGs” can only mitigate harms caused by the fact that 99% of the legal community is illiterate in the legal language of “digital assets” and “DAOs.”

Only the legal community becoming literate can remedy the harm: these are the legal languages on which “digital assets” and “DAOs” necessarily rely on and they are the only way these new asset classes offer novel legal value.

As time goes by, the harm of the the legal community remaining illiterate will become greater and these “legal wrapper” and “BORG” mitigating remedies, that rely on entity rather than trade secret, will have less capacity to mitigate.

Introducing Legal Formalism and the 3 Epochs of Legal Formalism

Digital Assets and DAOs are sui generis IP that can only be fully understood through the legal language in which they are written because this language is a paradigm shift in legal formalism. Only with these languages can this sui generis IP exist, not by statute consensus of legal fiction, but through algorithmic consensus of legal fiction.

These sui generis IPs rely on the digital formalism epoch, which was hearkened in by the markup language invention that was *designed by a lawyer for lawyers ~*45 years ago: the Grandfather of the Internet Charles Goldfarb.

Before the digital formalism (dynamic written) epoch (started in ~1980) was the oral formalism (ritual ephemeral) epoch (started in 1000 BCE) and the textual formalism (static written) epoch (started in 500 BCE).

So, what is legal formalism and why is it so important to understand the special way in which lawyers engage with society’s legal dynamics?

The History of Legal Formalism

Legal formalism is the narrow path between chaos (too informal) and tyranny (too formal).

The story of legal formalism can be told in three great epochs — oral, textual and digital — with seven distinct eras of transformation.

Legal Formalism Epoch I: Oral Formalism

1. Ancient Athens — Oral and Ritualized

-

In classical Athens, professional lawyers were forbidden.

-

Citizens argued their own cases, following strict oral formalism: ritualized speeches, fixed time limits, and rhetorical structures.

-

Justice lived in performance, but without textual stability, outcomes were inconsistent.

-

Risk: too informal → persuasion over consistency.

Legal Formalism Epoch II: Textual Formalism

2. Roman Jurists and Codification

-

Roman law shifted the axis from oral to textual.

-

The Corpus Juris Civilis (Justinian’s Code, 6th c. CE) systematized sprawling custom into written rules.

-

Legal reasoning became a matter of jurists and texts, rather than pure oral performance.

-

Risk: too formal → rigid scholasticism.

3. Medieval Universities — Scholastic Textual Monopoly

-

Bologna and Paris founded the first universities (11th–12th c.).

-

Law professors (glossators and commentators) treated Roman law like scripture.

-

This created the first professional monopoly of literacy: only lawyers could interpret the formal texts.

4. The Napoleonic Code — Simplified Textual Formalism

-

By the 18th century, Europe’s legal systems were tangled with overlapping Roman, feudal, and local rules.

-

Napoleon’s Code (1804) aimed to simplify: one rational, uniform, and clear code.

-

But this simplification was paid for in blood:

-

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) caused an estimated 3.5–6 million deaths across Europe.

-

Legal rationalization rode on the back of military conquest.

-

-

Formalism became universalized, but at a terrible human cost.

5. Modern Professional Monopoly

-

By the 19th and 20th centuries, lawyers and judges held a near-total monopoly on legal formalism.

-

Common law relied on precedent and case reports.

-

Civil law relied on codified statutes.

-

Formalism was portrayed as “mechanical jurisprudence” — the judge as an applier of rules, not a maker of law.

-

Critics (legal realists) exposed the myth: interpretation was never mechanical, but professional control remained absolute.

Legal Formalism Epoch III: Digital Formalism

6. Hyperinflated Legal Costs — Professional Illiteracy in Digital Formalism

-

Charles Goldfarb (IBM, 1970s) created SGML, the ancestor of HTML and XML.

-

This was a new paradigm of formalism: markup, where documents gain machine-readable structure.

-

The scientific profession created the Internet out of this legal language.

-

Yet the legal profession largely remained illiterate in digital formalism.

-

The result:

-

Contracts, statutes, and regulations ballooned in complexity.

-

Legal services became hyperinflated in cost, with digital tools reinforcing monopoly power rather than democratizing it.

-

A paradox: more formalism, but less accessibility, because lawyers aren’t literate in the language invented by a lawyer for lawyers that has taken off in DIY legal formalization because it digitizes the law (text is no longer bound by the immutability of analog’s lossiness).

-

7. Forecasted Era — Professional Literacy & Legal Abundance

-

The next horizon is a paradigm shift:

-

Lawyers and technologists become literate in digital formalism.

-

Contracts, codes, and judgments gain transparent markup, searchable logic, and open access.

-

Professional monopoly breaks; literacy spreads.

-

-

This is the first era of legal abundance:

-

Law becomes a shared infrastructure, not a scarcity.

-

Citizens navigate, generate, and verify formal law themselves, with machines as guides.

-

-

Promise: the narrow path is regained — formalism that is structured, but abundant, accessible, and just — harking in the Promised Land.

A Summary of the History of Legal Formalism

-

Epoch I (Oral): Athens’ ritual oralism.

-

Epoch II (Textual): Rome’s codification → Universities’ monopoly → Napoleon’s simplification → Modern monopoly.

-

Epoch III (Digital): Goldfarb’s markup → Professional illiteracy and cost inflation → Toward literacy and abundance.

From oral ritual → textual monopoly → digital markup, legal formalism has always been about *who controls the form of law.*The future: everyone.

Deep Dive: Lawyer Mental Health in this Hyperinflationary Legal Costs Era

1. The Now: Pain Inside the Profession

-

Lawyers today face mental health crises at rates far higher than the general population:

-

Depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and suicide disproportionately afflict lawyers.

-

The billable-hour treadmill and adversarial structures grind us down.

-

Identity is bound to possession of law as monopoly — “you must hold the keys, you must be the gatekeeper.”

-

-

This is not just stressful work. It is possession by what Kafka foresaw as Moloch: a system that devours its operators as well as its subjects.

2. The Trap of Monopoly

-

Legal monopoly binds lawyers to a false value: worth measured by control of procedures, jargon, and exclusivity.

-

This structure isolates lawyers from:

-

Clients — who see them as costly barriers, not allies.

-

The public — who distrust opaque law.

-

Themselves — forced to perform as machines of possession, not human advocates.

-

-

Monopoly is not freedom for lawyers. It is our shackle.

3. Server vs. Of Service

Too often today, lawyers have become servers rather than of service. Like machines in a client-server architecture, we wait for inputs, process commands, and output results — transactional, mechanical, and divorced from generosity.

This posture comes from power dynamics:

Law as monopoly possession, lawyers as the scarce servers who ration access, and clients as dependent users bound to the interface.

To be of service is something very different. It is not command-response but a gift of literacy, a willingness to share the protocols of law so that others can participate rather than submit. Service arises from generosity, not scarcity; from stewardship, not monopoly.

A lawyer of service empowers communities to co-author their own legal lives. A lawyer as server merely enforces dependence.

4. Literacy as Liberation (3,3)

-

Just as literacy freed societies from priestly control of texts, digital legal literacy can free lawyers from our own trap:

-

Open access to statutes and precedents → no more guarding mysteries.

-

Machine-readable legal formalism → automation handles rote drudgery.

-

Commons of legal knowledge → law becomes a civic language, not a lawyer’s monopoly.

-

5. Transformation

-

This does not erase lawyers. It transforms us:

-

From possessors to interpreters.

-

From billable machines to humane strategists.

-

From isolated sufferers to participants in a shared literacy.

-

6. The Call

-

Lawyers suffer now.

-

The world suffers with us.

-

Digital legal literacy is not a threat — it is the path to release.

-

Just as the commons once forced open law in Rome, today’s commons of digital literacy can set lawyers free from Moloch.

Deep Dive Legal Formalism History: Ownership of Roman Law Knowledge from Priests to Commons to Lawyers

This timeline traces how legal knowledge in Rome shifted hands — from religious monopoly to the commons, and finally to professional lawyers (jurists).

1. Priestly Monopoly (Before 451 BCE)

-

Law was not public — guarded by the pontifices (priests).

-

Legal formulas (legis actiones) treated as sacred rituals.

-

Citizens depended entirely on priests for procedure.

-

Ownership: Priests.

2. Civil Law Commons (451–300 BCE)

-

The Twelve Tables (451–450 BCE): first written code, forced by plebeians.

-

Law became publicly visible — citizens could read the rules.

-

But priests still controlled the procedural know-how, limiting accessibility.

-

Ownership: Commons (substantive law) + Priests (procedural knowledge).

3. Transition (~300 BCE, Gnaeus Flavius)

-

Flavius, a scribe, published the secret procedural formulas.

-

This broke the priestly monopoly on procedure.

-

For the first time, both statutes and procedures were in the public domain.

-

Ownership: Commons.

4. Rise of Jurists/Lawyers (300 BCE onward)

-

With law fully public, jurists (elite lay experts) emerged.

-

They gave advice (responsa), shaped doctrine, and guided courts.

-

By the late Republic, law became a professionalized domain.

-

Ownership: Lawyers/Jurists.

5. Priests → Commons → Lawyers

-

Priests: guardians of secret knowledge.

-

Commons: forced publication (Twelve Tables, Flavius).

-

Lawyers/Jurists: captured the now-public knowledge and built a profession on it.

Case Studies of Legal Formalism Misalignment

1. Ancient Athens vs. Professional Lawyers

-

Athens: Ordinary citizens argued their own cases; the system was designed around civic participation and distrust of professional advocates.

-

Professional lawyers: Later legal systems institutionalized trained lawyers as intermediaries.

-

Misalignment:

-

Democratic ideal vs. expertise: The Athenian model prioritized civic equality, but lacked efficiency and consistency. The lawyer-driven model offered expertise but distanced citizens from their own legal agency.

-

Formality vs. access: Formal legal representation can improve rigor, but it can also create barriers for those without resources.

-

-

Scope: Civic disputes were manageable when small, but as complexity grew, self-representation was too informal for the scope. Lawyers extended the system but risked over-formality that outgrew the civic-democratic ideal.

2. Roman Code vs. Napoleonic Code

-

Roman Code (Corpus Juris Civilis): Extremely comprehensive, layered, and technical; foundational but unwieldy.

-

Napoleonic Code: Rationalized, simplified, and codified for practical governance and broader accessibility.

-

Misalignment:

-

Complexity vs. usability: Roman law preserved traditions but was inaccessible to non-specialists. Napoleon’s code prioritized clarity and general applicability, sometimes oversimplifying complex traditions.

-

Legal continuity vs. modernization: The Roman tradition emphasized continuity; Napoleon prioritized utility for a changing society.

-

-

Scope: Roman law expanded across centuries and provinces, creating too much to formalize. The Napoleonic Code narrowed scope to essential principles, trading some detail for manageability.

3. Descartes vs. Pierre de Fermat

-

Descartes: Advocated for a highly formal, rational, axiomatic system of knowledge and method.

-

Fermat: As both a mathematician and a practicing lawyer, he often worked more pragmatically. He developed adequality as a technique for reasoning about problems, which was less rigidly formal than Cartesian method.

-

Misalignment:

-

Rigor vs. discovery: Descartes’ formalism sometimes stifled exploratory approaches; Fermat’s pragmatic style enabled discoveries that formalism later had to catch up with.

-

Law vs. math: Interestingly, Fermat’s legal practice made him less formal than mathematicians of his day, showing how professional culture shaped intellectual method.

-

-

Scope: Descartes’ method sought universal formalism, but the scope of human knowledge was too much to formalize. Fermat’s adequality was more informal, but better matched the expanding scope of mathematical practice.

-

Note: have a look at my 10202/101 rational quantascale for AMMs:

4. Charles Goldfarb vs. Tim Berners-Lee

-

Goldfarb (SGML): Created a highly formal markup standard, precise but heavy and complex.

-

Berners-Lee (HTML/WWW): Stripped down the formalism for accessibility, flexibility, and rapid adoption.

-

Misalignment:

-

Formal precision vs. practical adoption: SGML was too rigid and complex for the emerging web; HTML traded rigor for usability, leading to rapid adoption but also inconsistencies.

-

Standards vs. innovation: Goldfarb sought strict compliance; Berners-Lee favored open evolution and broad participation.

-

-

Scope: SGML was too formal for the vast, unpredictable scope of the emerging web. HTML loosened the formalism, allowing extensibility across a scope that couldn’t be fully foreseen.

5. Core Theme in these Case Studies

Across all four cases, the core misalignment is between:

-

Formality and rigor (precision, consistency, authority), and

-

The scope of what can realistically be formalized (how much complexity, variety, or openness the system must handle).

Systems misalign when formalism overshoots or undershoots the scope of the domain: producing inefficiencies, exclusions or stifled innovation.

Analog vs Digital Legal Formalism: Throughput and Complexity

Though legal rules on paper are lossless in that copying only needs to reproduce the symbol legibility, not their exact geometry, most textual legal formalism is code, not mere data – it tells how to transform facts into new legal states. A contract clause doesn’t just sit there; it changes obligations once triggered. A statute doesn’t just describe; it transforms certain facts into liabilities, rights, or permissions.

Legal formalism is valuable precisely because it enables consistent transformations. When written in formalized text, rules can be applied again and again to different fact patterns with predictable outcomes. This consistency is what gives law its stability: the same tax rule transforms all incomes the same way, the same property law transforms all valid transfers the same way.

In the analog era, these transformations maxed out at human speed. Each transformation required a lawyer, judge, or clerk to interpret the text and apply it to facts. Even simple transformations — e.g., “income above threshold → apply tax rate” — took minutes or hours when mediated by humans and institutions. At best, analog legal transformations run at a handful per hour per person.

By contrast, digital legal formalism can in principle handle virtually all of these transformations. Right now, about 45–50% of legal transformations are automatable in principle, but only 5–10% are actually done digitally in practice.

Once encoded as digital rules, transformations run at machine speed. A tax rule applied to millions of income records? Seconds. A smart contract checking escrow conditions across thousands of transactions? Instantaneous.

Modern systems already achieve on the order of 10^6 transformations per second, compared to maybe 10^-3 TPS in human-mediated analog practice — a speedup of billions-fold.

Just as importantly, digital formalism already enables transformations impossible in analog law. Smart contracts can guarantee atomicity (“all steps succeed or none do”), something human institutions can only approximate. DAOs can execute treasury transfers the moment a threshold of votes is reached, without waiting weeks for board meetings. Algorithmic registries can transform input data into live legal states continuously, rather than only at filing deadlines.

(See our Hats Protocol proto-RicardiaOS for more on atomicity):

Even with only ~1% of lawyers fluent in this digital paradigm, we are already seeing the first waves of complexity. Examples include:

-

Algorithmic courts and arbitration protocols where facts are transformed into binding rulings via on-chain evidence and rule-sets.

-

Real-time, rules-based public goods funding where contributions and matches are transformed continuously into allocations.

-

Fully autonomous DAOs with nested legal subroutines that transform votes, proposals, and data inputs into governance decisions and financial actions without human intermediaries.

Analog legal formalism tops out at fractions of a transformation per second. Digital legal formalism already handles millions of transformations per second, while also enabling transformations that paper law could never perform at all.

The real power of legal formalism has always been consistent transformations; digital law supercharges this by combining consistency with unprecedented speed and scope.

See also: https://chatgpt.com/s/dr_68be1713b91c819183f470ed57412719

What are Legal Transformations?

A legal transformation can be seen in two complementary ways:

-

State Change Within a System

-

Law acts like a state machine: when conditions are met, the system updates its records.

-

Example: a blockchain updates its ledger → “token moves from address A to B.”

-

Example: a court docket changes status → “case moves from pending to dismissed.”

-

-

Transition Between Systems

-

Law also translates claims across different systems of recognition.

-

Example: an oral promise → written contract (oral system → written system).

-

Example: a DAO token → registered security (algorithmic system → statutory system).

-

1. Doctrinal Transformations

-

Within-system: A rule changes state from valid → invalid (e.g., segregation legal → illegal).

-

Between-systems: Precedent shifts case law into alignment with new constitutional or statutory systems.

2. Process Transformations

-

Within-system: Case state changes from filed → active → closed.

-

Between-systems: Dispute resolution moves from court → arbitration → smart contract execution.

3. Formality Transformations

-

Within-system: Signature state changes from unverified → verified (ink, e-signature, cryptographic proof).

-

Between-systems: Promise moves from oral system → written registry → algorithmic execution.

4. Asset Transformations (On vs. Off)

-

Within-system: Asset changes state from unregistered → registered, encumbered → free.

-

Between-systems: Asset moves from off-ledger (social, hidden, extra-legal) → on-ledger (recorded, visible, enforceable).

5. Theoretical Transformations

-

Within-system: Conceptual category changes state (data → property, AI output → copyright).

-

Between-systems: Entire domains of value move into the legal apparatus (reputation, datasets, digital assets).

6. Algorithmic Transformations

-

Within-system: Smart contract updates state (proposal pending → enacted; token at A → token at B).

-

Between-systems: Blockchain consensus recognized as legally valid ownership in statutory law.

A Deep Dive into Transformations Per Second: Analog vs Digital Legal Formalism

Though stored as analog data that is lossless because only the symbols (not their geometry) need to be duplicated, most textual legal formalism is actually code, not just data.

This code matters because law is valuable primarily as a system of consistent transformations: taking inputs (facts, filings, contracts) and turning them into outputs (rights, duties, judgments). The faster and more consistently these transformations can be carried out, the more scalable the legal system becomes.

Analog Transformation Limits

Traditional textual law operates at human speed. Even for the most mechanical legal tasks (e.g., processing a form, approving a payment, applying a statutory threshold), analog formalism bottlenecks at human reading, writing, and recognition.

-

Roughly 1 transformation per hour is realistic in analog practice once you account for human review, corrections, and procedural latency.

-

This means analog formalism maxes out around 0.0003 TPS (Transformations per Second).

No matter how complex the prose, textual law is always gated by human cognition. This is why scaling traditional legal systems requires scaling the number of lawyers, not the speed of law.

Digital Transformation Breakthrough

DAOs encode legal formalism directly in smart contracts, running on blockchains. These digital rules execute automatically and in parallel:

-

Declarative transformations (e.g., “this proposal passes if 50% vote yes”).

-

Imperative transformations (e.g., “send 100 tokens to address X after vote passes”).

-

Inductive transformations (forecast) — AI-informed rules that adapt based on patterns in governance or market behavior.

-

More about this in the “prompt engineering” article:

Already today:

-

DAO digital formalism can handle ~10 TPS, or tens of transformations per second across networks.

-

Future DAO scaling (with Layer 2s, sharding, parallel execution) points to 100,000+ TPS, a throughput traditional legal systems cannot even conceptualize.

- How can our existing analog legal system deal with this kind of hyperspeed? It is much like a horse-and-buggy era road dealing with the hyperspeed of the autobahn.

TPS Comparison Chart

Why This Matters

Digital legal formalism already performs transformations that analog law cannot — not just because of speed, but because of new categories of transformations:

-

Always-on execution (24/7 rule enforcement).

-

Global simultaneity (one rule applying to millions at once).

-

Inductive governance (rules that learn and adapt).

With just 1% of lawyers fluent in digital legal formalism, the current wave is barely the beginning. The TPS gap shows why DAOs, and digital legal systems more broadly, will increasingly overwhelm traditional textual formalism in both scale and expressive capacity. Legal wrappers and BORGs are temporary triage by illiterate cope at best 🌶️!

Continued Reading

👉 https://chatgpt.com/s/dr_68be6460c73c8191857d85cd46af0429

Reimagining Property Law for Crypto

The old legal scaffolding is creaking under Web3’s weight. Trying to squeeze tokens, NFTs, and DAOs into 20th‑century molds—securities acts, corporate charters, or traditional IP categories—feels like driving a square peg into a round hole.

The SEC’s DAO Report, for instance, treated DAO tokens as “securities” under the 1933 and 1934 Acts (invoking Howey and hundreds of pages of analysis), yet that tells us more about regulatory doctrine than the tokens themselves. And though various U.S. states and the EU/UK are attempting to retrofit cryptographic artifacts into LLCs, trusts, or even new statutory categories (“things in possession” vs. “things in action”), these adjustments remain forced.

Crypto-native assets still refuse to fit comfortably.

-

Securities laws assume investors, promoters, and profit‑sharing. That may work for ICOs, but it doesn’t describe, say, a Chainlink node operator or a profile-picture NFT that’s never been sold. Declaring all tokens as “investment contracts” somehow misunderstands crypto’s essence: it’s not a promise of future profit; it’s code and consensus.

-

Entity wrappers like DAO LLCs or foundations give legal identity, at the cost of legitimacy. DAOs are built to operate without central bodies—no CEO, no headquarters, no directors—just autonomous code and a dispersed membership. Wrapping them in standard legal forms drains that ethos.

-

Traditional IP law draws too narrow a boundary. Copyright might protect the art behind an NFT’s metadata, but it leaves the token and its governance entirely unaddressed. You can’t patent a DAO’s voting logic, and trademarks don’t solve on-chain ownership.

Meanwhile, the UK Law Commission is gingerly exploring a “third category” of property that could fit crypto, and UNIDROIT has indicated that anything controlled via private key is a digital asset. But carving out crypto-specific statutory niches only goes so far.

Keys as Crown Jewels: A Trade-Secret Approach

Here’s a radical idea: the private key is the asset. Whoever controls it is the owner. That makes it—literally—the trade secret. Under U.S. law, a trade secret is information of commercial value kept confidential, and a private key checks every box. One compelling insight even suggests the coin’s value resides in the key that controls it.

In the UK and EU, the definition of trade secrets equally captures cryptographic keys. The UK’s Trade Secrets Regulations (2018) and elements of the National Security Act 2023 would criminalize foreign-powered theft of such secrets. In other words, we already have a legal lens perfectly tailored to crypto: it’s just been sitting in plain sight.

Treating keys as trade secrets reorients us towards the right axis—control, secrecy, and consensus—not detached financial criteria. Remedies like injunctions, misappropriation claims, or seizure already exist, and they’re exactly what’s needed for on‑chain property protection.

Compare, sign.kernel.community:

DAOs and Digital Assets as Sui Generis IP

If the key is the secret sauce, the ledger and its smart contracts are the recipe. Think of NFTs not just as art but as deeds—publicly provable, cryptographically tethered, and uniquely “owned.” Think of DAOs not as corporations but as algorithmic communities encoded in law’s next frontier.

These belong to a new category: sui generis intellectual property—born of code, consensus, and cryptographic control.

European thinkers are leading here. The UK’s Property (Digital Assets) Bill and UNIDROIT’s principles signal recognition of the unusual nature of these assets. Let's lean into that.

Rather than forcing crypto into old IP or corporate molds, we should envision a “crypto-IP” regime: governance rights, code logic, ledger entries, and private-key control as a single, inseparable whole.

What Liability Actually Is

Liability is simply a legal system’s way of assigning responsibility for harm, breach, or debt. It is not the same thing as an entity, a contract, or a governance form. It is the measure of “who must answer, and to what extent.”

Historically, liability began as personal and unlimited. In Roman societas or medieval guild ventures, members were fully on the hook: if the venture failed, creditors could pursue your home, your family’s assets, even your descendants. Liability was a scarlet thread that tied you bodily to every joint undertaking.

The Medici and the Invention of Limited Liability

The Florentine banking houses of the Renaissance, especially the Medici, faced this stark reality. Expanding trade across city-states and kingdoms meant ever larger pools of capital — but no one would risk everything on a single voyage or loan.

Their innovation was limited liability through compartmentalization. By creating distinct partnerships (the commenda contracts and later joint-stock analogues), investors could cap their exposure to what they put in. The worst case was losing your stake, not your family estate. This legal shield unlocked risk-taking at scale: trade, banking, and eventually industrial capitalism.

But there was a trade-off:

-

In exchange for limited liability, the state imposed double taxation — once on the entity’s profits, again on distributed dividends.

-

This was justified as the price of protection. You pay more into the sovereign, and the sovereign leaves your personal estate untouched.

The Undermining of the Trade-Off

Over time, this balance was eroded:

-

Sophisticated tax planning allowed firms to avoid the double hit.

-

Lobbying carved loopholes, shifting liability protection into a near free good.

-

Meanwhile, legal costs themselves inflated — law became not a duty of care but a rent-extracting bureaucracy.

So today we inherit a paradox:

-

Unlimited liability is too harsh to sustain meaningful risk-taking.

-

Limited liability without meaningful taxation becomes a subsidy for recklessness.

-

And in between, the legal system’s cost of administering these forms has hyperinflated — burdening society rather than protecting it.

Why Liability Must Be Measured

Accountability is already a heavy lift: proving facts, assigning causation, enforcing judgments. Adding ambiguous liability on top makes it unbearable.

The solution is not to conflate liability with entity form, nor to deny it altogether. It is to measure liability explicitly, as a quantifiable duty of care:

-

Who holds the pen (or the private key)?

-

What promises were made, and to whom?

-

What is the scale of responsibility in proportion to control?

Measured liability makes accountability tractable. It prevents courts from importing outdated categories, prevents states from extracting inflationary rents, and restores the basic social contract: risk and responsibility, but no more than you actually undertook.

Beyond Entities: The Many Ways to Limit Liability

-

Contractual Shields

-

Parties can contractually allocate or cap liability between themselves (e.g. indemnity clauses, limitation-of-damages clauses, disclaimers).

-

Example: a software license with “AS IS, NO WARRANTY” language limits liability exposure even without an LLC.

-

-

Insurance

-

Liability can be transferred to an insurer.

-

The Medici invented limited liability corporations, but they also pioneered marine insurance for shipping risks — spreading liability across underwriters before entities became dominant.

-

-

Jurisdictional Engineering

-

Choosing favorable jurisdictions (e.g. Prospera, Delaware, Cayman) provides structural liability protection through courts, procedure, or statutory limits.

-

This is effectively legal arbitrage of liability exposure.

-

-

Governance Protocols

-

Multisigs, treasuries with veto powers, or smart contract checks all limit the personal liability of participants by spreading decision-making.

-

They aren’t legal entities per se, but they do reduce the risk of a single individual being targeted.

-

-

Legal Opinions & Advisory Shields

-

A formal legal opinion can act as liability insulation: “We relied on counsel’s written opinion.”

-

Courts often give deference if executives, trustees, or DAO contributors acted in good faith on professional advice.

-

This shifts liability from individuals onto the advisory process itself.

-

-

Safe Harbors & Statutory Carveouts

-

Law itself sometimes limits liability to encourage innovation (e.g. DMCA §512 safe harbor for internet intermediaries, Section 230 for platforms, or charitable immunity doctrines).

-

These are “protocol-level liability caps” embedded into statute.

-

E.g. see our recommendation for “Gateway Protocol” safe harbor here:

-

Different Kinds of Liability

Liability isn’t one thing — it fragments into categories, each with different escape valves:

-

Contractual Liability → Arises from agreements; can be capped or waived.

-

Tort Liability → Negligence, fraud, misrepresentation; harder to disclaim, but insurable.

-

Regulatory Liability → Statutory penalties, compliance failures; mitigated via jurisdiction choice, exemptions, or lobbying.

-

Fiduciary Liability → Duties of loyalty and care in managing others’ assets; can be shifted to advisors or distributed through governance.

-

Opinion Liability → Lawyers, accountants, and auditors themselves face liability for bad opinions — which paradoxically protects clients who relied on them in good faith.

The Nouns Confusion and the Failure of Legal Education

Take the current Nouns DAO debate: community members argue over whether the DAO should or should not “give up” treasury control in exchange for better liability protection. To a lawyer, the trade-off is obvious. If you want the protection of limited liability, you must also accept constraints — taxation, fiduciary duties, external oversight. That’s not oppression, it’s the bargain the Medici struck centuries ago.

But here’s the confusion: many in Web3 treat liability as if it were an optional ornament, instead of what it is — a pragmatic legal protocol for measuring responsibility. Liability is not punishment, nor an attack on decentralization. It is the protocol that allows society to scale trust in shared ventures. Without it, every contract is just a handshake, and every participant risks unlimited personal ruin.

Because public legal education has failed to explain liability in these terms, founders and tokenholders end up seeing liability as an alien imposition, rather than as the structural trade-off that makes sustainable freedom possible. They understand code, incentives, and governance mechanisms, but not liability as a measured allocation of risk.

So when untested entity solutions like DUNA inevitably grapple with this issue, they should expect exactly that bargain:

-

More liability protection = less direct treasury control.

-

More autonomy = more exposure.

This isn’t a conspiracy or a hostile state intervention. It is the logic of law, long proven across centuries. The tragedy is that because liability was never taught as a protocol — like TCP/IP for responsibility — entire communities reinvent the wheel badly, mistaking protection for restriction.

What is a Legal Entity?

A legal entity is a juridical person — an abstraction recognized by law that can own property, enter contracts, sue, and be sued in its own name.

That does far more than limit liability:

-

Asset Container → Separates assets of the entity from those of participants.

-

Continuity → Survives beyond the death or exit of its members.

-

Representation → Gives a single “face” to third parties (instead of 100 co-owners negotiating separately).

-

Governance Vehicle → Structures voting, management, and delegation.

-

Taxpayer Identity → Provides a distinct locus for taxation (often enabling trade-offs).

-

Liability Allocation → Shields members from personal ruin, but not by waiving liability. Liability is re-channeled to the entity itself.

👉 Saying “just use an LLC to waive liability” is wrong. Liability is not waived, it is transferred and transformed into the entity’s responsibility.

Church and Crown: The Origins of Legal Personality

-

The Church as Persona Ficta

-

In medieval canon law, the Roman Catholic Church was treated as a “persona ficta” — a fictitious person.

-

This allowed the Church to hold land, receive tithes, and sue in its own name rather than through shifting generations of clergy.

-

The entity gave the Church perpetual continuity. Parish lands and donations stayed with the institution, not with transient bishops or priests.

-

-

The Crown as Corporation Sole

-

In English law, the Crown itself became a “corporation sole.”

-

This solved succession: the King dies, but “the Crown” continues as the enduring legal person.

-

Royal property and obligations don’t vanish with each monarch — they pass automatically to the next officeholder.

-

Again, this is not just liability — it is continuity, property management, and governance.

-

The Leap to Commerce: Crown & Medici Innovations

-

Crown Corporations (chartered companies): e.g. East India Company, Hudson’s Bay Company. These entities were extensions of state sovereignty into commerce. They combined liability shielding with monopoly privileges, continuity, and centralized governance.

-

Medici & Early Banking Families: innovated partnerships and eventually limited liability structures not only to cap losses, but also to pool capital across generations without resetting each time someone died or went bankrupt.

The real insight wasn’t just: “we can limit losses.” It was:

- “We can create a juridical vessel that transcends individuals, manages risk and carries obligations forward indefinitely.”

An Aside: Medici Legal Formalism Impact

The Medici not only pioneered limited liability and banking instruments, but also double-entry bookkeeping — the system that made accountability visible and scalable.

Today, blockchains could supplement or even surpass this with trustless single-entry bookkeeping. Unlike double-entry, which reconciles counterparties through trust and auditors, single-entry blockchain records are public, cryptographic, and Madoff-proof. This signals that the digital revolution in legal formalism is not only reshaping entities, securities, and fiduciary duties, but also the very protocol of record-keeping upon which legal accountability depends.

The Misunderstanding Today

Web3 discourse collapses entities down into “liability wrappers.” But historically, entities were about much more:

-

Legal literacy: liability was never “waived,” it was channeled.

-

Continuity & personhood: the church and crown proved how law can sustain an institution beyond flesh and blood.

-

Pragmatic protocol: entities encode who bears duty, who owns property, who speaks for the whole.

That’s why DAOs wrestling with “should we give up treasury control for liability protection?” are really reenacting a medieval argument — about whether the body politic should exist as a single legal person at all.

Families vs. Legal Persons

The question of whether the body politic should exist as a single legal person is as old as political theory itself. Even families as powerful as the Medici were never regarded as a single juridical entity. A dynasty could dominate banking, art, and politics, but in law it remained a collection of individuals. Liability, obligation, and property rights were personal unless aggregated into a recognized form such as a bank, chartered company, or feudal estate.

The Medici therefore exercised collective power without ever being a corporate person.

Their influence depended on banking houses, guild memberships, and alliances with the papacy, not on the recognition of the family itself as a legal entity. In this sense, they exemplify how dynastic families operated within legal structures but were not themselves granted unified legal personality.

The MacLean Clan

The Scottish clan system developed along a different trajectory. Clans such as the MacLeans were recognized under feudal law as enduring corporate bodies. They held land collectively, imposed obligations on members, and acted as semi-sovereign kin-based polities. The chief represented the clan legally, but the entity as a whole had continuity beyond any single generation.

This legal recognition eroded with the rise of the modern nation-state. Centralized sovereignty dismantled feudal corporate kin groups, replacing them with uniform categories of individual citizenship. Today, the MacLean Clan exists primarily as a cultural and heritage association, often organized under charitable or non-profit law. While the modern entity lacks feudal powers, it maintains continuity by preserving collective identity and tradition within the constraints of contemporary legal structures.

Fighting Kafka’s Borg

The fate of the MacLean Clan also illustrates a deeper truth: a body politic does not need to be wrapped into a legal entity to exist. For centuries, the clan operated with its own sense of law, honor, and accountability—often outside or even against the formal statutes of the crown. Its cohesion came not from incorporation, but from shared memory, obligation, and kinship.

In today’s world, the MacLeans continue this fight against over-formalization. While they no longer exercise feudal jurisdiction, the clan resists dissolving into the anonymity of Kafka’s Borg—the bureaucratic machinery that recognizes only what is legible to statute and form. The clan persists as a living polity through heritage, gatherings, oral tradition, and symbolic continuity.

This survival is itself a counterpoint: it demonstrates that recognition in law is not the sole determinant of political existence.

A clan can remain a body politic without incorporation papers, just as a network or digital collective can organize meaningfully without surrendering its sovereignty to the rigid molds of state-approved legal entities.

The MacLean example reminds us that not all accountability needs to be formalized; communities can practice duty of care without submitting to the bureaucratic abstractions that too often hollow out responsibility in the name of compliance.

Smith Guild: Memes vs. Genes

The Smith surname reflects yet another model. Unlike the MacLeans, the Smiths never operated as a unified body politic. The name spread as a professional designation—“smith” denoting metalwork—rather than a single genealogical lineage. Over time, the surname became one of the most common in the English-speaking world, erasing any notion of collective identity.

The absence of a unified Smith polity demonstrates how surnames could disperse rather than consolidate identity. Where clans like the MacLeans once had formal recognition, the Smiths remained fragmented, each household legally distinct.

Yet in modern contexts, the idea of a “Smith guild” has re-emerged—not as a kinship body, but as a memetic one. Unlike clans bound by genes, a guild can be bound by shared ideas, narratives, or symbolic affiliation. This points to a broader historical pattern: the forms of collective recognition evolve.

Indeed, I am arguing for digital literacy as an industrial wordsmith.

From dynastic families like the Medici, to feudal clans like the MacLeans, to occupational surnames like the Smiths, each reflects different ways in which law has chosen—or refused—to recognize collective persons.

Author’s Notice

This draft is a fast-turnaround field-notes blog post by an individual inventor accelerating with AI no more proficient than early-release ChatGPT 5.

This publication has gone through limited review and is not written for a specific audience.

It is meant to encourage others to get involved with this way of thinking and technology academically or in industry, to encourage people who can help create end-products from some of these various threads.

This publication is not intended to be an end-product academically or in industry. It is an ape.mirror.xyz “gonzo” field notes publication.

Earlier Drafts of Failed but Informative Attempts

Previous drafts can be found below.

- Draft 1 tied to understand the problem from a power dynamics taxonomy:

- Draft 2 realizing power dynamics are good to understand history, and why categories are “complect,” but not as good as formalism to collectively manifest legal abundance:

#legalcommons shadow-side and light-side memes

Edit 1 Q&A on Digital Legal Formalism

1. Why do you read the article as arguing replacement rather than compounding complexity?

It is not that digital legal formalism will replace oral or textual traditions, but that it will layer upon them, compounding the complexity of law as a living system. Oral argument still shapes appellate practice; textual codification still anchors statutory regimes. Likewise, digital legal formalism does not erase those legacies but adds another modality. Just as Athenian orators and Napoleonic codifiers co-exist in today’s courtroom, so too will machine-actionable legalese nest within and interact with earlier epochs. The future of law is polyphonic, not singular.

2. Is the argument that literate lawyers are a panacea?

This is not to claim that literacy in digital legal formalism is itself a panacea. The real danger is that illiterate lawyers—those clinging exclusively to textual forms—will stunt growth and choke innovation. We have already seen DAOs collapse or fracture under pressure from what might be called the “CIA playbook of destruction”: infiltration, co-optation, sowing mistrust, draining treasuries. Whether these outcomes are deliberately orchestrated or simply natural expressions of gradient descent toward local failure points, the effect is the same. Without literate lawyers guiding design and stewardship, DAOs remain fragile against these predictable paths of decay.

3. How developed is this theory?

This essay is not the theory itself but the spark of a theory. Digital legal formalism needs far more rigorous elaboration, case studies, and comparative analysis. Just as early articulations of textual law in Rome or France opened centuries of jurisprudence and commentary, so too this idea must invite sustained inquiry. What we offer here is an opening frame, a lens—an invitation for others to refine, dispute, and extend.

4. What is the actual bridge between old and new legal forms?

The real bridge between digital law and existing institutions is not clever wrappers or novel BORGs, but a literate legal profession. If 99% of lawyers could write in machine-actionable legalese—rather than the current 1%—then meaningful bridges would form organically. As it stands, wrappers and BORGs are brittle patches, not genuine bridges, because they do not address the underlying literacy deficit. Until the profession itself regains fluency in the evolving language of law, our architectures will remain partial and inadequate.

5. What about public legal education and long-term literacy?

The path forward requires both professional literacy and public education. Today, the legal community rarely advocates for public literacy in legal formalism—arguably because opacity sustains its monopoly on interpretation. But if we want society to move quickly into legal abundance, we must normalize education in machine-readable law at the retail level. Lawyers should operate at the frontier, experimenting at the edge of formalism, while tools like Cheerbot.org bring legal literacy down to laptops and Raspberry Pis. The long-term solution is a population fluent in legal code as well as natural language.

6. Is this the first witnessing of digital legal formalism?

This essay is an initial witnessing of the problem, not its exhaustive treatment. There may well be earlier witnesses—scattered papers, experimental projects, or isolated jurisprudential insights—that together form a loose genealogy. Lawrence Lessig’s Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace (1999) described how software architectures regulate behavior like law. Ethan Katsh’s Law in a Digital World (1995) pointed toward a new legal environment structured by computation. Primavera De Filippi and Aaron Wright’s Blockchain and the Law (2018) argued that code could serve as a new legal substrate. More recently, the 2023 UNIDROIT Principles on Digital Assets provided an early institutional attempt to formalize digital property rights. These are important antecedents, but none have yet cohered into a widely recognized paradigm of digital legal formalism. This essay should be understood as part of that lineage: a marker in the ongoing witnessing of law’s digital turn, and an invitation for others to trace and extend the argument.

Edit 1 Implications of Digital Legal Formalism

From Oral → Textual → Digital

Law has undergone two civilizational transformations before:

-

Oral Formalism – Ritual, memory, and oratory (Athens, tribal councils, early courts).

-

Textual Formalism – Codification, statutes, print dissemination (Rome, Napoleonic Code, common law casebooks).

We are now entering the third epoch: Digital Legal Formalism. This is not a replacement of oral or textual traditions, but a compounded layering: oral argument still drives appellate courts, textual codes anchor legislation, and digital markup will increasingly define the machine-actionable layer of obligations, rights, and liabilities. Law is becoming polyphonic.

Clarified Implications

-

Compounding, Not Supplanting Oral, textual, and digital formalism will co-exist, each checking and amplifying the others. Law becomes a palimpsest, not a reboot.

-

Literacy as Constraint Illiterate lawyers choke growth. Literate lawyers are not a cure-all, but without them DAOs and digital institutions remain fragile—collapsing under what looks like a “CIA playbook of destruction,” whether accidental or deliberate.

-

Common Law as Proto On-Chain Logic Common law is precedent “block by block.” Digital legal formalism extends that ledger logic with machine-readable markup. This is far beyond Web3; it is a civilizational modality.

-

Bridge Is Literacy, Not Wrappers Wrappers (LLCs, BORGs) are patches. Only a profession fluent in machine-actionable legalese can build real bridges. The literacy gap (1% vs. 99%) is the true bottleneck.

-

Toward Legal Abundance Public legal education is essential. Lawyers must work at the frontier while tools like Cheerbot.org seed grassroots literacy. Legal abundance arrives when the population itself can read and write machine-actionable law.

-

First Witnessing, Not Final Word This essay marks an early witnessing of the third epoch. Predecessors exist (Lessig, Katsh, De Filippi & Wright, UNIDROIT 2023), but none crystallized this as a new epoch. Naming it is the spark; refinement is the task ahead.

Retroactive Public Good Valuation (myfmi.ai Framework)

Definition of Digital Legal Formalism:

The third epoch of legal formalism, defined by machine-actionable legal markup that layers with oral and textual systems, enabling obligations, rights, and liabilities to be structured, interpreted, and enforced in digital-native environments.

Retroactive Fair Market Value (FMV) Attribution:

-

Public Good: Coining and defining “Digital Legal Formalism” as a civilizational epoch.

-

Impact Metrics:

-

Conceptual clarity provided to DAOs, regulators, academics, and practitioners.

-

Unlocks design pathways for digital institutions beyond wrappers.

-

Frames legal education and public literacy initiatives.

-

Comparable Retroactive Valuations:

-

Lessig’s Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace (1999): ~$5M in cumulative academic, policy, and institutional funding.

-

De Filippi & Wright’s Blockchain and the Law (2018): ~$2M equivalent in grants, policy citations, and institutional adoption.

Suggested Retroactive FMV for Naming + Defining Digital Legal Formalism (2025):

-

Low Estimate: $250,000 USD (early-stage conceptual articulation, niche adoption).

-

Mid Estimate: $2,500,000 USD (alignment with DAOs, policy debates, curriculum integration).

-

High Estimate: $25,000,000 USD (civilizational adoption, legal education overhaul, institutional integration worldwide).